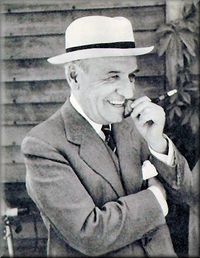

José Ortega y Gasset

|

|

| Full name | José Ortega y Gasset |

|---|---|

| Born | 9 May 1883 Madrid, Spain |

| Died | October 18, 1955 (aged 72) Madrid, Spain |

| Era | 20th century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Perspectivism, Pragmatism, Vitalism, Historicism, Existentialism |

| Main interests | History, Reason, Politics |

José Ortega y Gasset (9 May 1883 – 18 October 1955) was a Spanish liberal philosopher and essayist working at the beginning of the 20th century while Spain oscillated between monarchy, republicanism and dictatorship. He was, along with Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche, a proponent of the idea of perspectivism.

Contents |

Biography

José Ortega y Gasset was born 9 May , 1883 in Madrid. His father was director of the newspaper El Imparcial, which belonged to the family of his mother, Dolores Gasset. The family was definitively of Spain's end-of-the-century liberal and educated bourgeoisie. The liberal tradition and journalistic engagement of his family had a profound influence in Ortega y Gasset's activism in politics.

Ortega was first schooled by the Jesuit priests of San Estanislao in Miraflores del Palo, Málaga (1891–1897). He attended the University of Deusto, Bilbao (1897–98) and the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the Central University of Madrid, currently, Complutense University of Madrid (1898–1904), receiving a doctorate in Philosophy. From 1905 to 1907, he continued his studies in Germany at Leipzig, Nuremberg, Cologne, Berlin and, above all Marburg. At Marburg, he was influenced by the neo-Kantianism of Hermann Cohen and Paul Natorp, among others.

Upon his return to Spain (1909) he was named numerary professor of Psychology, Logic and Ethics at the Escuela Superior del Magisterio de Madrid and in October 1910 he was granted the Chair (Cátedra) in Metaphysics of the Complutense University, empty since the death of Nicolás Salmerón.

In 1917 he became a contributor to the newspaper El Sol, where he published as a series of essays his two principal works: España invertebrada (Invertebrate Spain) and La rebelión de las masas (The Revolt of the Masses); the latter made him internationally famous.

He founded the Revista de Occidente in 1923, remaining its director until 1936. This publication promoted translation of (and commentary upon) the most important figures and tendencies in philosophy, including Oswald Spengler, Johan Huizinga, Edmund Husserl, Georg Simmel, Jakob von Uexküll, Heinz Heimsoeth, Franz Brentano, Hans Driesch, Ernst Müller, Alexander Pfänder, and Bertrand Russell.

Ortega led the Republican intellectual opposition under the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923–1930), and he played a role in the overthrow of King Alfonso XIII in 1931. Elected deputy for the province of León in the constituent assembly of the second Spanish Republic, he was the leader of a parliamentary group of intellectuals known as La Agrupación al servicio de la república[1] ("At the service of the Republic"), but he soon abandoned politics, disappointed.

Leaving Spain at the outbreak of the Civil War, he spent years of exile in Buenos Aires, Argentina until moving back to Europe in 1945. He settled in Portugal by mid 1945 and slowly began to make short visits to Spain. In 1948 he returned to Madrid and founded the Institute of Humanities, at which he lectured.[2]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Development

History of liberalism

Contributions to liberal theory |

|

Ideas

Political liberalism

Political freedom Cultural liberalism Democratic capitalism Democratic education Economic liberalism Free trade · Individualism Laissez faire Liberal democracy Liberal neutrality Negative / positive liberty Market economy · Open society Popular sovereignty Rights (individual) Separation of church and state |

|

Schools

American · Anarcho-liberalism

Classical · Conservative Democratic · Green Libertarianism · Market National · Neoliberalism Ordoliberalism · Paleoliberalism Radicalism · Social |

|

People

John Locke · Adam Smith

Adam Ferguson Thomas Jefferson Thomas Paine · David Hume Baron de Montesquieu Immanuel Kant · Jeremy Bentham Thomas Malthus Wilhelm von Humboldt Frederic Bastiat John Stuart Mill · Thomas Hill Green Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse John Maynard Keynes Bertrand Russell Ludwig von Mises Friedrich von Hayek · Isaiah Berlin Joel Feinberg John Rawls · Robert Nozick |

|

Regional variants

Worldwide

Europe · United States By country |

|

Religious liberalism

|

|

Organizations

Liberal parties

Liberal International International Federation of

Liberal Youth (IFLRY) Alliance of Liberals and

Democrats for Europe (ALDE) European Liberal Youth (LYMEC)

Council of Asian Liberals and

Africa Liberal Network (ALN)Democrats (CALD) Liberal Network for

Latin America (Relial) |

Circunstancia

For Ortega y Gasset, philosophy has a critical duty to lay siege to beliefs in order to promote new ideas and to explain reality. In order to accomplish such tasks the philosopher must, as Husserl proposed, leave behind prejudices and previously existing beliefs and investigate the essential reality of the universe. Ortega y Gasset proposes that philosophy must, as Hegel proposed, overcome both the lack of idealism (in which reality gravitated around the ego) and ancient-medieval realism (which is for him an undeveloped point of view in which the subject is located outside the world) in order to focus in the only truthful reality (i.e. life). He suggests that there is no me without things and things are nothing without me, I (human being) can not be detached from my circumstances (world). This led Ortega y Gasset to pronounce his famous maxim "Yo soy yo y mi circunstancia" ("I am myself and my circumstance") which he always situated in the core of his philosophy. For Ortega y Gasset, as for Husserl, the Cartesian 'cogito ergo sum' is insufficient to explain reality—therefore the Spanish philosopher proposes a system where life is the sum of the ego and circumstance. This circunstancia is oppressive; therefore, there is a continual dialectical exchange of forces between the person and his or her circumstances and, as a result, life is a drama that exists between necessity and freedom.

In this sense Ortega y Gasset wrote that life is at the same time fate and freedom, and that freedom “is being free inside of a given fate. Fate gives us an inexorable repertory of determinate possibilities, that is, it gives us different destinies. We accept fate and within it we choose one destiny.” In this tied down fate we must therefore be active, decide and create a “project of life”—thus not be like those who live a conventional life of customs and given structures who prefer an unconcerned and imperturbable life because they are afraid of the duty of choosing a project.

Raciovitalismo

With a philosophical system that centered around life, Ortega y Gasset also stepped out of Descartes' cogito ergo sum and asserted "I live therefore I think". This stood at the root of his Kantian-inspired perspectivism, which he developed by adding a non-relativistic character in which absolute truth does exist and would be obtained by the sum of all perspectives of all lives, since for each human being life takes a concrete form and life itself is a true radical reality from which any philosophical system must derive. In this sense, Ortega coined the terms "razón vital" ("vital reason" or "reason with life as its foundation") to refer to a new type of reason that constantly defends the life from which it has surged and "raciovitalismo", a theory that based knowledge in the radical reality of life, one of whose essential components is reason itself. This system of thought, which he introduces in History as System, escaped from Nietzsche's vitalism in which life responded to impulses; for Ortega, reason is crucial to create and develop the above-mentioned project of life.

Razón Histórica

For Ortega y Gasset, vital reason is also “historical reason”, for individuals and societies are not detached from their past. In order to understand a reality we must understand, as Dilthey pointed out, its history. In Ortega’s words, humans have “no nature, but history” and reason should not focus on what is (static) but what becomes (dynamic).

Influence

Ortega y Gasset's influence was considerable, not only because many sympathized with his philosophical writings, but also because those writings did not require that the reader be well-versed in technical philosophy.

Among those strongly influenced by Ortega y Gasset were Luis Buñuel, Manuel García Morente, Joaquín Xirau, Xavier Zubiri, Ignacio Ellacuría, Emilio Komar, José Gaos, Luis Recaséns Siches, Manuel Granell, Francisco Ayala, María Zambrano, Agustín Basave, Máximo Etchecopar, Pedro Laín Entralgo, José Luis López-Aranguren, Julián Marías, John Lukacs, and Paulino Garagorri.

Ortega y Gasset influenced existentialism and the work of Martin Heidegger.[3]

German grape breeder Hans Breider named the grape variety Ortega in his honour.[4]

There have been two translations of The Revolt of the Masses into English. The first in 1932 by a translator who did not provide his/her name. The first translation is generally accept to be J.R. Carey. [5] The second translation was published by the University of Notre Dame Press in 1985 in association with W.W. Norton & Co. This translation was carried out by Anthony Kerrigan (translator) and Kenneth Moore (editor), with and introduction by Saul Bellow. Mildred Adams is the translator of the main body of Ortega's work, including Invertabrate Spain, Man and Crisis, What is Philosophy, Some Lessons in Metaphysics, The Idea of Principle in Leibniz and the Evolution of Deductive Theory, and An Interpretation of Universal History.

Works

Much of Ortega y Gasset's work consists of course lectures published years after the fact, often posthumously. This list attempts to list works in chronological order by when they were written, rather than when they were published.

- Meditaciones del Quijote (Meditations on Quixote, 1914)

- Vieja y nueva política (Old and new politics, 1914)

- Investigaciones psicológicas (Psychological Investigations, course given 1915-16 and published in 1982)

- Personas, Obras, Cosas (People, Works, Things, articles and essays written 1904-1912: "Renan", "Adán en el Paraíso" -- "Adam in Paradise", "La pedagogía social como programa político" -- "Pedagogy as a political program", "Problemas culturales" -- "Cultural problems", etc., published 1916)

- El Espectador (The Spectator, 8 volumes published 1916-1934)

- España Invertebrada (Invertebrate Spain, 1921)

- El tema de nuestro tiempo (The theme of our time, 1923)

- Las Atlántidas (The Atlantides, 1924)

- La deshumanización del Arte e Ideas sobre la novela (The Dehumanization of art and Ideas about the Novel, 1925)

- Espíritu de la letra (The spirit of the letter 1927)

- Mirabeau o el político (Mirabeau or politics, 1928–1929)

- ¿Qué es filosofía? (What is philosophy? 1928-1929, course published posthumously in 1957)

- Kant (1929–31)

- ¿Qué es conocimiento? (What is knowledge? Published in 1984, covering three courses taught in 1929, 1930, and 1931, entitled, respectively: "Vida como ejecución (El ser ejecutivo)" -- "Life as execution (The Executive Being)", "Sobre la realidad radical" -- "On radical reality" and "¿Qué es la vida?" -- "What is life?")

- La rebelión de las masas (The Revolt of the Masses, 1930)

- Rectificación de la República; La redención de las provincias y la decencia nacional (Rectification of the Republic: Redemption of the provinces and national decency, 1931)

- Goethe desde dentro (Goethe from within, 1932)

- Unas lecciones de metafísica (Some lessons in metaphysics, course given 1932-33, published 1966)

- En torno a Galileo (About Galileo, course given 1933-34; portions were published in 1942 under the title "Esquema de las crisis" -- "Scheme of the Crisis"; Mildred Adams's translation was published in 1958 as Man and Crisis.)

- Prólogo para alemanes (Prologue for Germans, prologue to the third German edition of El tema de nuestro tiempo. Ortega himself prevented its publication "because of the events of Munich in 1934". It was finally published, in Spanish, in 1958.)

- History as a system (First published in English in 1935. the Spanish version, Historia como sistema, 1941, adds an essay "El Imperio romano" -- "The Roman Empire").

- Ensimismamiento y alteración. Meditación de la técnica. (This title is not easily translated, because the title uses a neologism and there is a play on words. Literally, it is "Sameness-making and alteration", but it could also be read as "The making of sameness and difference." In either case, the subtitle means "A meditation on technique." 1939)

- Ideas y Creencias (Ideas and Beliefs: on historical reason, a course taught in 1940 Buenos Aires, published 1979 along with Sobre la razón histórica)

- Teoría de Andalucía y otros ensayos • Guillermo Dilthey y la Idea de vida (The theory of Andalucia and other essays: Wilhelm Dilthey and the idea of life, 1942)

- Sobre la razón histórica (On historical reason, course given in Lisbon, 1944, published 1979 along with Ideas y Crencias)

- Prólogo a un Tratado de Montería (Preface to a Treatise on the Hunt [separately published as Meditations on the Hunt], created as preface to a book on the hunt by Count Ybes published 1944)

- Idea del Teatro. Una abreviatura (The idea of theater, a shortened version, lecture given in Lisbon April 1946, and in Madrid, May 1946; published in 1958, La Revista Nacional de educación num. 62 contained the version given in Madrid.)

- La Idea de principio en Leibniz y la evolución de la teoría deductiva (The Idea of the Beginning in Leibniz and the evolution of deductive theory, 1947, published 1958)

- Una interpretación de la Historia Universal. En torno a Toynbee (An interpretation of Universal History. On Toynbee, 1948, published in 1960)

- Meditación de Europa (Meditation on Europe), lecture given in Berlin in 1949 with the Latin-language title De Europa meditatio quaedam. Published 1960 together with other previously unpublished works.

- El hombre y la gente (Man and the populace, course given 1949-1950 at the Institute of the Humanities, published 1957; Willard Trask's translation as Man and People published 1957; Partisan Review published parts of this translation in 1952)

- Papeles sobre Velázquez y Goya (Papers on Velázquez and Goya, 1950)

- Pasado y porvenir para el hombre actual (Past and future for the man of today, published 1962, brings together a series of lectures given in Germany, Switzerland, and England in the period 1951-1954, published together with a commentary on Plato's Symposium.)

- Goya (1958)

- Velázquez (1959)

- Origen y epílogo de la Filosofía (Origin and epilog to Philosophy, 1960),

- La caza y los toros (Hunting and Bullfighting, 1960)

See also

- Liberalism

- Contributions to liberal theory

References

- ↑ Encarta Encyclopedia Spanish Version: Agrupación_al_Servicio_de_la_República Microsoft Corporation Spanish Version [1]. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Philosophy Professor: Jose Ortega Y Gasset

- ↑ The Dehumanisation of Art Princeton University Press 1972 page 146.

- ↑ Wein-Plus Glossar: Ortega, accessed 13 April 2008

- ↑ as referenced by the Project Gutenberg eBook of U.S. Copyright Renewals, 1960 January - June.

External links

- Online English Edition of Revolt of the Masses

- Fundación José Ortega y Gasset Spain

- Fundación José Ortega y Gasset Argentina

- Project Gutenberg

]

|

|||||||||||||||||